![]()

![]()

![]()

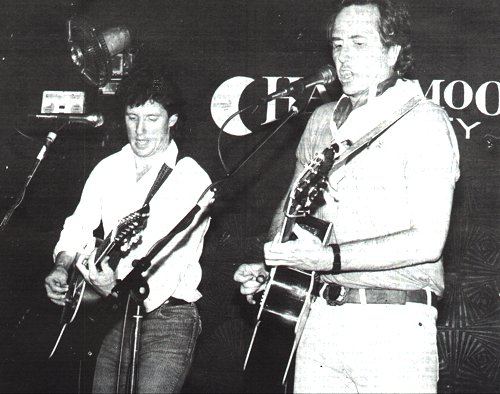

SPENCER

LEIGH: I couldn't believe my ears when BBC Radio Merseyside's chief

engineer, Bill Holt, told me that John Stewart had been booked to appear

at the Floral Pavillion New Brighton on Sunday 5 August. What's more,

the concert was to be recorded for future broadcast.

SPENCER

LEIGH: I couldn't believe my ears when BBC Radio Merseyside's chief

engineer, Bill Holt, told me that John Stewart had been booked to appear

at the Floral Pavillion New Brighton on Sunday 5 August. What's more,

the concert was to be recorded for future broadcast.

To help promote the concert, John's LPs were obtained from the BBC Gramaphone Library in London and they were handed from presenter to presenter in the days leading up to the concert. John Stewart could be heard as regularly as the news, and I presented an appreciation of his work called "Fire in the Wind."

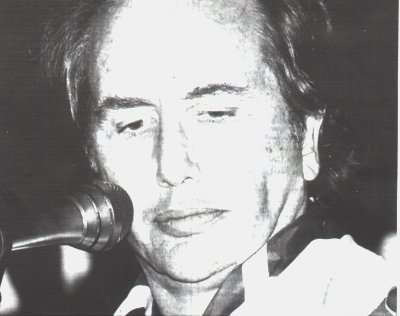

John Stewart, his wife Buffy and son Luke were duly booked into the Holiday Inn, opposite Radio Merseyside. I'd arranged to meet him shortly before midday on the Sunday and take him across the road for an interview. It would be for a programme in my series, "Almost Saturday Night," a one hour show that would be half-music, half-chat. I only needed 30 minutes' conversation but I'd booked the studio 'til 2 o'clock. There were scores of questions I wanted to ask and I didn't propose to waste the opportunity.

I was with my friend, photographer and John Stewart devotee, Andrew Doble. We got under way with a coffee and John signed some albums, usually with a pertinent quip. On "California Bloodlines" he wrote, "Why is this man laughing?" On "Phoenix Concerts," "Would you invite these men to dinner?" "Wingless Angels" was "from Wing Commander Stewart," and "Bombs Away Dream Babies," "From a friend of Stevie Nicks." He wrote, "Me doing my Bogart," on the cover of "Fire in the Wind," and that was a revelation for a start. I'd always assumed he was impersonating Clint Eastwood!

The tapes began rolling at 12.15 and please bear in mind that this is a radio interview for a music programme. Five minutes of straight conversation is not good radio, and so our talk had to be steered towards music, and the selection of particular tracks, at regular intervals. I've added the titles to this transcript and you might like to play them as they arise. That way, it'll take you all evening to wade through the interview!

Similarly, aspects of John's life and thoughts which do not relate to music are hardly covered. For example, I don't ask about his childhood in any depth and, when I do, it's to find out the rock 'n' roll performers he saw - another excuse for music! Also bear in mind that I'm thinking more of Radio Merseyside listeners than Omaha Rainbow readers so I can't ask anything too obscure. Furthermore, I try to keep myself out of my interviews as much as possible because it's the subject and not the interviewer that the public want to hear. Besides, I'm too busy with the controls to fully concentrate on what John is saying.

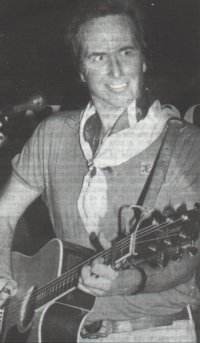

I'm glad to say that the interview turned out great, and afterwards we took John for a quick tour round the centre of Liverpool. He called the rebuilt cavern Club 'holy ground" and expressed an interest in playing there. Andy took a photograph of him offering a cigarette to the statue of Eleanor Rigby.

Back at the Holiday Inn, we had lunch with John, Buffy and Luke.

I use the word 'lunch' loosely. The food was a disgrace and even

though a lot of Stewart food swopped plates, no one was happy. Indeed,

I wondered if John would have been better off with the "two-dollar gins."

John kindly paid the bill (£25), which I took to be a sign that he'd

enjoyed the interview.

There was more good conversation as we ate. John has the ability

to sum up a performer in a few succinct phrases. For example, he

described Bruce Springsteen as a mixture of Bob Dylan and Dion. He

thought he'd like Elvis Costello's songs, ".....but I never listen hard

enough. I can't stand his voice." Commenting on the guitar

break in Police's 'Every Breath I Take,' he said, "First" time I heard

that record I said, 'When did I do this?'. He hadn't enjoyed Paul

Simon's "Hearts and Bones" LP but he thought Dire Straits' 'Telegraph Road'

was terrific. He said he wouldn't fly Virgin, "Wel1, would you trust

your life to a record label?"

The New Brighton concert was excellent, and John was captivated by the support act, Hank Walters with his Dusty Road Ramblers. Hank has been playing country music on Merseyside since 1948. John Lennon once said to him, "I don't go much on your music, but give us your hat."

Six hundred people attended the concert, a mixture of hard-core John Stewartites, Hank Walters fans, and New Brighton holidaymakers. Some complained that John wasn't performing singalong country music, but most were very satisfied. The following day a taxi-driver called out to me and showed me the John Stewart albums he'd just purchased. He knew how St Paul felt on the road to Damascus!

The recording of the show by Bill Holt has come out excellently and is likely to be broadcast on Radio Merseyside as a Christmas special. I hope, too, that it will appear as an LP on Sunstorm Records!

Because I've been involved in series about Liverpool music and the Merseybeat era, it doesn't seem likely that I'll be broadcasting another series of "Almost Saturday Night'' until May 1985. I hope that some of you get to hear the John Stewart programme because, although it makes good reading, it's even better to hear John laughing and singing snatches of songs. Let's hope the broadcast will coincide with John's next visit.

* * * * * * * * * *

San Diego is a naval town, a coastal town in California, a very pretty city surrounded by hills and trees. I only lived there a year or so and then we moved up to Pomona in Pasadena, California, so I don't remember San Diego as it was then. I go back a lot but my youth was really spent in Riverside and in Pasadena.

You wrote a song about childhood, 'The Pirates of Stone County Road.' Was that autobiographical?

In a way it was. When you're a young lad you can be anywhere and turn it into anything you want it to be. All our imaginations are running wild, and so I would do things like that, but the song is really more a part of America that is no more - and probably never was. The Nebraska, Kansas part of America with its quiet afternoons and two-storey houses, the porches with the swing, the old swimming hole and all of that. That is so indicative to America and is a part of a heritage that we all hold on to.

(Play 'The Pirates of Stone County Road' - John Stewart)

I believe your father owned a racehorse.

My father was a horse-trainer. He trained for other people and then he owned some of his own.

So songs like 'Let the Big Horse Run,' 'Back in Pomona' and 'Mother Country' presumably stem from your childhood experiences?

Yeah. I grew up on the racetrack and I grew up around horses. My father's obsession was horses and so they were all around me. I'd work on the racetrack after school or on the weekends and all summer, so I spent a lot of time there when I was a boy.

In 'Mother Country' someone wants to ride a horse one more time before he goes blind. Was that based on fact?

Yeah, but he drives the horse. Riding you're on top of it, driving you're in a cart behind. It's an absolutely true story and my father was there when it happened in Pomona. He worked with E.A. Stuart and E.A. Stuart owned Sweetheart on Parade, which in reality was known as

(Play 'Mother Country' - John Stewart)

Did you see many rock 'n' roll performers in your youth?

I saw Elvis Presley at the Pan Pacific Auditorium in LA when 'Hound Dog' was out, you know, he still had the stand-up bass and the Jordanaires, and it was unbelievable. I was shaken by the concert. I had never seen anything like it in my life. I mean, all that energy coming off the stage, and his voice was so strong and he was having so much fun doing it. And I went down and saw Fats Domino when he came to the Rainbow Gardens in Pomona one night and that was another element. He was so relaxed, you know, he came out with the big rings and smiling all the time - (Sings) "I want to walk you home, please let me walk you home" - and I thought, 'Wow! Rock 'n Roll!' And I can remember a big show at the Pomona Fairground with the Kingston Trio - 'Tom Dooley' had just come out - and Johnny Cash, this lean, hungry guy singing 'I Walk the Line.' And there was The Champs doing 'Tequila,' a group called The Teddy Bears with Phil Spector - (Sings) "To know, know, know him is to love, love, love him" - and Ritchie Valens doing 'La Bamba.' He died with Buddy Holly and I'm sorry that I never got to see him.

My favourite rock 'n' roller was Gene Vincent. Did you get to see him?

Never got to see him, no.

He toured here with Eddie Cochran.

Oh, Eddie Cochran. You know, when 'Summertime Blues' came out I thought, 'Oh my God, who is this guy? It's great!' Same with the Everly Brothers - one hit after another and each one different from the one before. That's what I miss now, Spencer, a record used to come out and totally blow me away. I mean, I would be shaken by it. The world would always look different to me because of that record, and that doesn't happen to me anymore.

(Play 'Summertime Blues' - Eddie Cochran)

Did you play rock 'n' roll yourself?

Yeah, I had a rock 'n' roll band in high school and I really loved playing the old songs, although of course they weren't old at that point. Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, I played them all, so some of my roots are really in rock 'n' roll. Folk came along while I was in college and it was indeed the music of the college people at that time. You didn't have to carry equipment around. You could do it with one guitar, and you could have a group with just a couple of guitars. The songs had very singable choruses and were fun to do, but they also told stories and had adventure to them. I was captivated by that aspect and also by the 5 string banjo, this totally alien instrument to me, with its magic, dronal sound. So I quickly went from rock 'n' roll to folk music and became totally obsessed by that music.

And before you joined the Kingston Trio you were writing songs for them.

Right. Well, everytime they came in town I would go backstage, and one day I did and they loved these two songs that I had written, 'Molly Dee' and 'Green Grasses.' They recorded 'Molly Dee' on their next album. I was just out of high school and this royalty cheque came in. It was for more money than I could ever have made in a year working as a clerk or whatever and I thought, 'This is the way to do it. Are you kidding me?' So going to college was losing its allure. I was playing music all the time and after two years of college I dropped out and said, 'I don't want to do this. This is what I want to do.'

I presume that, in today's terms, the cheque would be quite small.

No, it was a good and healthy cheque. If you got that cheque today, you'd have to sit down. The album was number one and the Trio was selling albums like crazy at that time. At one time they had three albums in the top ten. If a group did that today, my God, they'd be called The Messiah!

Do you remember the day when you were asked to join them?

No, I don't really. I was in New York and I heard some rumours that Dave Guard might be leaving and I asked Nick what was going on. He said, "I don't know but keep in touch." So I did and he asked me to come out and audition. I flew out to Sausalito with my then wife Julie, who was pregnant, and we stayed at the hotel. I auditioned and then sat around for a couple of days. They called and said, "You've got the job."

Was 'Where Have All the Flowers Gone?' one of the first records you made with them?

No, that was a couple of years down the line. The album "Close Up" was the first album I did with them.

Let's have a song from "Close Up." What should we play?

Er, oh. (Brightly) Oh, 'Reuben James,' without a doubt.

(Play 'Reuben James' - The Kingston Trio)

Had Pete Seeger written 'Where Have All the Flowers Gone?' sometime before you recorded it?

Pete Seeger wrote the music. Anton Chekhov, the great Russian poet, had written the words. We were in Boston, playing in town, and we went to a folk club there. A new group called Peter, Paul and Mary were appearing and there were only about eight people in the audience. They did 'Where Have All the Flowers Gone?' and we all went, 'Are you kidding me?' We heard that Pete Seeger had written it and so we knew it had to be on a Pete Seeger album somewhere. I dug it up and wrote the chords out. We learnt it immediately and went into the studio within ten days and recorded it. Peter, Paul and Mary have never forgiven us for that.

Was it a controversial song at the time?

Yes, in a way it was. Anti-war sentiments were not as popular then as they are now.

And it's as relevant now as it was then.

It will always be relevant. It would have been relevant ten thousand years ago and it will always be relevant.

(Play 'Where Have All the Flowers Gone?' - The Kingston Trio)

Staying with anti-war songs, do you remember when you first heard Bob Dylan?

Oh, clearly, clearly. We were in New York and Dylan was the enfant terrible of the Village at that time. Everyone would congregate in this bar called The Dug-Out and Phil Ochs would say, ''That's Dylan over there." He'd walk in and slink over and he'd keep very much to himself. He had a single out at the time called 'Corrina Corrina' (Sings in a Dylan voice) "Where you been so long?" We thought, this is unbelievable, and we were very much aware of him. 'Blowin' In the Wind' was the first real Dylan song that caught us and I still think 'The Times They Are A-Changin" is one of the most powerful records recorded by anyone, yet it's just one guitar and one voice. But in all the years I've never met Dylan. Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman, once sent me a tape of some Dylan songs for the Trio to record. One of them was 'Mr. Tambourine Man' and I confess I sent it back and said, "I have no idea what this guy's talking about.''

Do you think he's influenced your own writing?

No, no, not at all, and I'm very easily influenced too. There are some writers out there that I respect and they do what they do so well that it's never really translated to what I was writing.

(Play 'The Times They Are A-Changin'' - Bob Dylan)

You mentioned Phil Ochs. Did you know him?

I knew Phil. I knew Phil very well.

He was a tragic case.

Very tragic and there was a very sad irony right before he died. One of the great blows to him was that this apparent revolution was going to take place in America with Huey Newton and Abbie Hoffman leading it, and that's what Phil always wanted to do. He wanted to be the leader of the new revolution. Of course, the revolution never did work out, and they're all back selling stock and have day jobs and cut their hair, but for a time it looked for the media and all the movement that there was going to be a revolution. Phil wasn't at the front of it and that really tore at him because he was one of the first to be thinking in those terms, that America should be shaken up, you know.

And what's a song that's representative of the way he thought?

'I Ain't Marching Anymore.'

(Play 'I Ain't Marching Anymore' - Phil Ochs)

We'll come back to the Kingston Trio's records now and to something I've wanted to know for 20 years. You can tell me the answer.

I hope I know!

What does 'Ally Ally Oxen Free' actually mean?

'Ally Ally Oxen Free' is a term used in America for hide and go seek or kick the can. You put a can in the middle of the street, you all go hide and someone has to go and find you. If you can run back and kick the can before the searcher gets back to hold the can down, you're the first one and you can yell "Ally Ally Oxen Free." That means, 'Everyone come on in. We've won the game.' It means, 'We've won,' yeah.

(Play 'Ally Ally Oxen Free' - The Kingston Trio)

It sounds like you had a lot of fun recording 'Reverend Mr. Black.'

It was a lot of fun. There were only three or four records that we ever got from people sending in material and 'Reverend Mr. Black' was one of them. It was sent in on a demo by Billy Edd Wheeler, a great, great American songwriter who later wrote 'Coward of the County' for Kenny Rogers.

And you're doing the narration.

Yeah, and Glen Campbell's playing 6 string banjo on it and is singing the tenor parts. Glen Campbell was one of the best LA sidemen. 'Reverend Mr. Black' was one of those cases when you know you've got a hit.

(Play 'Reverend Mr. Black' - The Kingston Trio)

You wrote a song with John Phillips called 'Chilly Winds.'

A couple of songs.

How did that come about?

John had a group called The Journeymen and he was hanging around San Francisco at the same time as me. We became best friends and because we were both writing songs like mad, we did some things together. I brought in a song called 'Oh Miss Mary,' like (Sings) ''Mary, Mary, where are you?" and John had a title called 'Chilly Winds.' We went out in a boat in San Francisco Bay in Sausalito with a bottle of wine one afternoon and we wrote verse upon verse for this song, then we stayed up all night writing some more. Truly, we had fifty or sixty verses to it, then we pruned it down to four. It was a great time.

(Play 'Chilly Winds' - The Kingston Trio)

I love a John Phillips' track called 'Mississippi.' Do you know it?

Oh, great song. That whole solo album he did is a classic. It's an astounding album.

And yet he never followed it up.

Well, I heard he cut some tracks with Mick Jagger producing, and having Mick Jagger produce John Phillips is like having General Eisenhower direct a nursery school. A little overkill. John is a very sensitive writer and a great friend of Jagger's, I guess, and it was a fun project but you're right, he hasn't followed up. It's something that everone who loves that album wishes he had done.

(Play 'Mississippi' - John Phillips)

Everybody listening will know a song you wrote 'Daydream Believer.' You were performing folk music with the Kingston Trio and suddenly you've written a pop hit. Had you planned it at all?

It's a good example of how we put labels on things because we need to identify them. 'Daydream Believer' was written as a folk song and it was written as part of a suburbia trilogy. It happened that a friend of mine, Chip Douglas, who also had auditioned for Dave Guard's place in the Kingston Trio, was now producing The Monkees and he said, "John, do you have any songs?" I said, "I have this one song that would be terrific, 'Daydream Believer'." I played it for him and he said, "Yeah, absolutely!" They went in and recorded it and put it in a rock 'n' roll mode by using the 'Help Me Rhonda' hornline. (Demonstrates) It was a rock 'n' roll song but it was a folk song. If you play it with one guitar it's a folk song. If you play it with a band it's a rock 'n' roll song, so can you tell me what rock 'n' roll is, what folk is? It all depends on what you put behind it.

(Play 'DaydreamBeliever' - The Monkees)

You mentioned that 'Daydream Believer' was part of a trilogy. What happened to the other songs?

They weren't very good. (Laughs)

Can we know what they were?

Yeah, one was called 'Do You Have a Place I Can Hide?' At the time I knew I would be leaving the Trio. I wanted to go out and be a singer/songwriter but I didn't really want to be a solo just yet, and so John Denver and I were going to sing together as a duo. We rehearsed and among the songs we rehearsed were 'Daydream Believer,' 'Leaving on a Jet Plane' and 'Do You Have a Place Hide?' Somewhere there's a demo of John Denver and me doing that song, but I've no idea where it is. The other song in the trilogy was called 'Charlie Fletcher,' which was an indictment of suburbia, very 1960's you know, the Simon and Garfunkel era, people-with-day-jobs-don't-really-know-where-it's-at and all that baloney.

After the success of 'Daydream Believer,' were you tempted to write songs specifically for The Monkees?

I think it was on the last album The Monkees did. You're always trying to write that song but the problem is, Spencer, that when I wrote 'Daydream Believer,' I remember thinking clearly that I didn't get much done today, all I did was write 'Daydream Believer.' I took the song to Spanky and Our Gang and to We Five, but they turned it down. No one heard it as a hit. I just thought it was another catchy little tune but once it was a hit, everyone heard it as a hit. ''Why don't you write another 'Daydream Believer'?" I can't do it unless, of course, I write another song that sounds exactly like 'Daydream Believer.' I just keep writing songs and I never know which will be the songs that will really connect. There are songwriters who can sit and write hit records. Neil Sedaka and Carole King can grind them out, but I've never been that kind of writer.

You mentioned We Five. I think I'm right in saying your brother was part of that group.

Yes, my brother Michael was a member.

They had a big hit in the States with ,You Were on My Mind,' although it was covered here by Crispian St Peters. Can you tell me something about the song?

It was written by Sylvia Fricker of Ian and Sylvia, and when Mike was putting the group together he asked me if I had any songs. I said,'''You W'ere on My Mind' is a terrific song, Michael, but you should do it like an old Ronettes' tune. You know, (Sings) 'Woke up this morning, you were on my mind, whoa, whoa' ." He's a great arranger so he took it and gave it a drumbeat and put all those vocal harmonies on. Now, when we played 'Blowin' In the Wind' for Frank Werber, our manager and producer, he said, ''That's the worst song I've heard in my life so we're not going to put it out." When Michael brought in 'You Were on My Mind' - Frank Werber, poor man, he's in America and can't defend himself - said, ''Why are you bringing me this crap?" (Laughs)

(Play 'You Were on My Mind' - We Five)

Going back to the Kingston Trio, I'd like to know what you think of "The New Frontier" album?

I think that is the best Trio album that I was associated with. "College Concert" has a live feel and a sound to it that is probably the best Trio album of that era, but we really worked on "The New Frontier" and I think the songs are very good. It was the first time I was really aware of what you could do in a studio. There's a song on there called 'Honey, Are You Mad At Your Man?' which included a couple of Appalachian tunes, 'Ruby' and something else, and used one note on the banjo against these moving chords, very Fleetwood Macish. It really worked in the studio because of the echo and things, but it wouldn't work in concert. Before then it was always, "Do the song, do it in concert and if it works, record it." With "New Frontier" I saw for the first time that you could do things in a studio that didn't have to translate to concerts. To me, that album was a real highpoint.

(Play 'Honey, Are You Mad At Your Man?' - The Kingston Trio)

I get the impression from the later Kingston Trio albums that you were making a takeover bid for the group. Certainly your sleeve notes for the LP "Children of the Morning" give that impression.

It wasn't a bloodless coup or anything like that. They just weren't that interested. Bobby Shane had moved to Georgia and they were driving racecars and shooting skeet. I was a songwriter and I was always the one who wrote out the chord charts and so more responsibility came my way, which I loved. I wanted to do it anyway and it just sort of went that way.

On "Children of the Morning" album, you perform 'Norwegian Wood.' What made you choose that song?

'Cause we loved it. The only reason we ever did a song was 'cause we loved it. We didn't care that the Beatles had done it and that we weren't breaking new ground. Nick and I loved the song and we wanted to sing it, so we sang it.

(Play 'Norwegian Wood' - The Kingston Trio)

When the Kingston Trio disbanded, am I right in saying that you teamed up as a duo with Buffy Ford?

No, I didn't work with Buffy until about a year-and-a-half later. I was looking to put a group together and I was looking to sing with a female voice. I loved the female quality that the Weavers and Peter, Paul and Mary had. I'd been part of three men singing together for seven years and I was real tired of that sound. I wanted the upper colour that you get with a female and I looked all over, girls from Canada and New York, but couldn't find anyone. Then I finally found Buffy eight miles away from where I lived.

Had you known her for some time?

No, never met her before. The group was going to be me and Buffy and a fellow named Henry Diltz, who became a member of the Modern Folk Quartet with Chip Douglas and is now one of the really well known photographers.

He took the cover of "Trancas."

Yeah. Anyway, it just wasn't working out with Henry. He was really a photographer and my writing had become more personal, more my own vision. Buffy and I sounded really good together and so at that point it became a duo with Buffy and I.

The album you made together, "Signals Through the Glass,'' still sounds good today. One track I particularly like is 'Cody.' Was that based on someone you know?

Actually it's based on a character in "The Red Pony," the Steinbeck novel. This old man who led the wagons to the sea is a very classic American character and 'Cody' was also Buffalo Bill Cody, who was synonymous with the old West. 'Cody' is a sort of compilation of a lot of people.

(Play 'Cody' - John Stewart and Buffy Ford)

I've read that you and Buffy were working on the Kennedy campaign in 1968 but, being English, I find it hard to understand what that involves.

I met Robert Kennedy when he was Attorney General and I was with the Trio. I'd kept in touch with him and he was very kind and kept in touch with me. When I left the Trio, he had run for Senator in New York and I had campaigned there. I would go out at a rally and sing a few songs. Then, when he was running for President, he said ''Would you and Buffy come out and sing for me?" and we said, "Of course." We dropped the album we were making - just put it on hold - and we would fly into a town with him. We would get off the plane and dash to the rally where there would be people who had been waiting two, three or four hours to see Kennedy. They were tired and restless and we'd give them a point of focus and get their energy up, so that when Kennedy arrived they wouldn't be so splintered. It was a dog and pony show but it was politics. We were there as the court jesters if you like, the travelling band.

(Play 'Clack Clack' - John Stewart)

A few years ago Paul Gambaccini conducted a poll amongst rock critics, asking them for their favourite LP's, "California Bloodlines" came in at number 36. Were you aware of this?

I was. I was floored by it. I couldn't believe it. It was a good feeling.

Were you surprised that they chose "California Bloodlines"? Is that the album that stands out for you?

No, it isn't. I'm always surprised at the reaction to that album and, even today, I can't sit through it. I think it has a good feel and that the songs are good, but my performance on it is dreadful. I tell you, it was a lot of fun to make the record and Nik Venet should take full credit for that. After the "Signals Through the Glass" album he said, "No, no, John, let's go to Nashville and get a live feel. The best players are down there." "California Bloodlines" was really his vision and it was really the first emergence of folk into country-rock, before the Eagles and all that, and I can take no credit for that. That was Nik's. He's an incredibly intuitive guy. He's a producer who's excellent for getting the best out of you, but he no real ideas in the studio, he simply lays down the format for you to come up with them. The album was done live apart from few vocal overdubs on 'The Pirates of Stone Road.' We made a two-track as we were doing the album and when we went back to mix it we couldn't get it as good as the two-track. We ended up using the two-track so it's pretty much a live album.

When you say your performance is ''dreadful,'' what do you actually mean by that?

Dreadful is dreadful, Spencer. For me, I just can't stand it, but that has nothing to do with anybody else liking the album. It's not important that I like it. My view has nothing to do with that someone coming in with a clear board would have to think about it. I have a backlog going into it.

Do you think your voice sounds different on this album?

Oh, it's gotten better. I've finally learned how to somewhat sing. I don't know. I was always surprised at the reaction to "California Bloodlines" because it was so other to what was going on at the time. That was one of its strengths, I imagine, but at the time it didn't sound like anything that anyone else was doing. Nobody else was writing songs like 'Mother Country,' 'Omaha Rainbow' and 'The Pirates of Stone County Road.' I just thought, 'What is this?' 'cause I was into other groups and I thought lots of other people were terrific. I knew that "CaliforniaBloodlines" didn't sound like them, so how good could it be?

'Razor Back Woman' is one of the oddest songs I know. How did you come to write it?

It's a bit autobiographical. I was immersed in those hardbitten American characters that Steinbeck created, and so I was taking a bit of my own childhood and embroidering on it and making it more colourful.

(Play 'Razor Back Woman' - John Stewart)

Do you recall how you came to write 'July, You're a Woman'?

I know exactly how I came to write it. I was really taken by the chord progression on 'Gentle on My Mind,' the rollingness of it, (Hums) I love the roll on that. I'm also sure that there was some character or somebody that I was totally smitten with at that time - I can't remember who. "I can't hold it on the road'' was the feeling I remember from high school when sex was something that happened to other people. You could really get high just dancing close with somebody, or just making out, or just being with them, 'cause that was as far as it was going to go and the tension would get incredible.

And I really wanted to write a song about the Great American Fantasy - that you're driving down the road and there's a girl by the highway and you pick her up and this magic happens and you're never seen again. You know, "a gypsy girl named Shannon," and all this. I was also in love with Steinbeck and these great colourful characters, Doc and the boys in "Cannery Row.'' I could lose myself in characters that were larger than life and, to me, that was what made the book fun. And there was a great movie called "The Rainmaker'' with Burt Lancaster who plays Starbuck, which was real magical to me, so in essence I wanted to write a song like 'Gentle on My Mind' and I wanted to include these characters in it.

You've mentioned Steinbeck a few times. Did you try your hand at novel-writing yourself?

Oh, no, no, no, no. I don't have the discipline for that.

'July, You're a Woman' was covered almost immediately by Pat Boone.

Pat Boone did it, also a group called Red, White and Bluegrass. Who else did it? John Wilkinson did it. Robert Goulet recorded it.

What's his version like?

I've never heard it. I can imagine what it's like but I've never heard it. 'July, You're a Woman' is a real enigma now, Spence, because recently I was sending some tapes to Nashville to see if I could get a record deal to do some country records. I did a new version of 'July, You're a Woman' that I real1y love and the record company said, "Well, that song's been a hit too many times." It's never been a hit! It was in the top 40 country charts four times, but everyone thinks it was a hit and therefore won't record it. Gordon Lightfoot has the same problem with 'Early Morning Rain.' Everyone thinks it was a hit but it never was. I don't know what that has to do with anything. It's just a little meaningless trivia.

(Play 'July, You're a Woman' - John Stewart)

You've yet to mention the title song on the album, 'California Bloodlines.'

'California Bloodlines' is one of those songs that is just given to you. Sometimes I feel that I really don't write these songs at all because, when I start writing, a whole other person comes out who is nothing to do with me during the workaday world. If I were to write songs about what I deal with everyday, they would be very different from what I write. When I start writing this other person comes out, and 'California Bloodlines' wrote itself. I think I wrote it in six minutes. I was playing around with a G tuning on the guitar and it just came out effortlessly, it flowed right out.

(Play 'California Bloodlines' - John Stewart)

Let's move on from "California Bloodlines'' to your second solo album, ''Willard.'' A lot of big names are playing on that album.

Oh yeah, that was a star-studded crew before they became big names. Well, Carole King was known because of her songwriting and James Taylor - very sweet guy, friend of Peter Asher's - happened to like my music and had just finished ''Sweet Baby James." He agreed to fly out from the East Coast to play on "Willard'' and I was living at Peter Asher's house while we were doing it. It was a very good time and it was very good to work with Peter. I drove him absolutely bonkers but he was very patient, and to play on an album with all those people was a great learning experience for me.

There's a great feel to the album and it sounds like you're having a ball on 'Golden Rollin' Belly.

Oh we did, we absolutely did, no doubt. I'll tell you how the album came about. After "California Bloodlines," I did an album with Chip Douglas producing that Capitol rejected. They didn't want to put it out so I said, "I tell you what. Let me go back down to Nashville with the same guys that I did ''California B1oodlines'' with and let me produce an album." I went down there and I did an album that was not bad, I must say, and they said, "Look, John, you had great reviews with "California Bloodlines." Let's get a real good producer and do another album.'' Can you believe that? They were willing to scrap two albums and yet do a third because they thought they might have something. It'd never happen in today's market. I really wanted to work with Peter Asher because I'd heard "Sweet Baby James" and the Apple album he'd made with James Taylor and I thought they were terrific. So I went in with Peter and made the "Willard'' album, but we also used a couple of those cuts I'd done in Nashville. They were 'Belly Full of Tennessee' and 'Earth Rider.'

(Play 'Golden Rollin' Belly' - John Stewart)

Just before you came off Capitol you had a single released called 'Armstrong.'

Yeah, I did. Almost did it.

Did you write that at the same time as Neil Armstrong walked on the moon?

At the moment. I wrote it as it was happening. We went into the studio in two days and the record was out four days later. It's an example of when a big record company wants to do it, they can really do it, they can crank it out. Everyone took 'Armstrong' the wrong way. Everyone took it as a putdown of the Moonshot, which was not intended at all. The message of the song was that even though there are ghettoes in Chicago and people are starving in India and we've completely ravaged the planet, we could for one moment sit there and watch one of our kind walk on the moon. Where we have really failed, we have also succeeded greatly, but everyone took it as a putdown of the Moonshot. It was banned on radio stations and stations were breaking the record on the air. It got on the charts, like at number 80, and the next week it was up to number 50. It was on its way and then it disappeared. It was banned by stations all over the country. I think I should have made the song more clear.

Did you ever get any feedback from Armstrong himself?

Never, no, I never did. I would love to have met him but I never heard a word.

(Play 'Armstrong' - John Stewart)

You moved to Warner Brothers and your first album for them was "The Lonesome Picker Rides Again" in 1971. It's one of my favourite albums. Is it one of yours?

To tell you the truth, Spence, I'm not happy with many of them. A couple maybe, but not that many. I like some of the songs on that album. I think 'Wild Horse Road' and 'All the Brave Horses' are good. And I like 'Freeway Pleasure' and 'Wolves in the Kitchen.' What else is on it?

'Just an Old Love Song.'

Oh, that's alright.

'All the Brave Horses' could have been a hit for you, don't you think?

Naw, no, I don't think so. It doesn't have hit qualities. It's too heroic and there's not enough variety in it.

Was it inspired by a particular death?

It was about what we had gone through with the Kennedys and Martin Luther King and the irony that the best people are so often shot down in their prime. Yeah, absolutely.

(Play 'All the Brave Horses' - John Stewart)

In complete contrast, there's a delightful song on "The Lonesome pickerRides Again" called 'Bolinas.'

I like 'Bolinas' and I did it with Buffy. Bolinas is a great, little seacoast town in California. The inlet is like glass, it's very quiet and time slows down. There are good things on that album.

(Play 'Bolinas' - John Stewart and Buffy Ford)

It sounds like you're giving "The Lonesome Picker Rides Again" the thumbs-up, so how about your second album for Warners, "Sunstorm''?

I hate it. I absolutely hate that album.

But you can't have hated it while you were making it?

Yeah, I did. It never worked right from the word go and I guess it should have been stopped at that point, but you're in there and you're spending a lot of money and the record label wants an album. You can't just pull out, you know. It's just that sometimes you don't get your momentum going. It happens with everything - it happens with a date, it happens at parties, it happens on the job. Some days just don't go right. Well, this whole project to me was always bogged down. I was working with my brother Michael, who is a very talented producer, but working with your brother is not like working with a stranger because you know too much about each other. There's too much backlog of being kids together, you know, so we didn't have that advantage of distance so, to be candid with you, I never really liked the album at all. Oh, I like the cut my father did.

That's the account of Haley's Comet.

Yeah, I think that was a terrific record because it was very real. I was going to do it like 'Mother Country' and do the narration myself, but listening to the tapes of him telling the stories, I thought, 'This is what it is. This is real.' So we just took the two hours I had of him telling the story, put it onto two track, edited like crazy and wove that into the song.

(Play 'An Account of Haley's Comet' - John Stewart)

Then you moved to RCA and made the album, "Cannons in the Rain."

"Cannons in the Rain, " yeah, I love that album.

Quite a few people have commented on the vibrato in your voice. Is that an effect you deliberately put in?

No!! It's something that I try desperately to get rid of!

I think it's one of the attractions of your work.

See, I've always hated it. I've always tried my best to get rid of it. Never totally did but pretty well gotten rid of it now. I loved doing the "Cannons in the Rain" album which I did with Fred Carter, a great guitar player out of Nashville. He played on a lot of Simon and Garfunkel records - that great opening on 'The Boxer' is his. He's an old friend and it was one of the first albums that I really had a hand in producing. Fred and I produced it. I've always believed that an album should have a mood and a texture to it and this was the first album that I had done that I thought had a mood from beginning to end. We made it in the great RCA Victor studios down in Nashville, great warm chambers, and we really thought the album out and we really worked on it and tried to lean it up and bring some colour to it. I think we succeeded. It's a good album.

James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson starred in the Sam Peckinpah film, "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,'' and it's clear from the song that you wrote, 'Durango,' that you were being considered for the film.

I had Dylan's role. I had it, my bags were packed, I met the producer, he liked me and said, "You're going to go to Mexico.'' I talked to Kris and he said, (Impersonates Kr'istofferson's voice) ''Oh yeah, it'll be great, John. We'll be down there, we'll have a lot of fun.'' I was ready to go, then I got a call and the producer said, "John, I'm sorry but Dylan has agreed to do it." I said, ''Ah, well, he'll be terrific." In retrospect, talking to Kris afterwards, it turned out to be a miserable time. Peckinpah wouldn't leave his trailer for five days at a time, the wind was blowing and they all got colds, but it sure would have been fun to work with Coburn and Peckinpah and Kris. But Dylan was terrific, I thought did a great job.

I thought it was a good film very moody.

Very moody. For the people listening at home, I've just spilled my coffee all over my pants. I'll be fine when the blisters heal.

(Play 'Durango' - John Stewart)

'All Time Woman' is one of my favourite songs.

Ah, I like that song, yeah, written about Buffy.

And life on the road.

Life on the road and the vacant lot it really is, and how finding one person you can love and be friends with is really what it's all about.

Does Holiday Inns and two-dollar gins sum up a rock musician's life?

When you wake up in the morning and there's a half-consumed glass of alcohol next to your bed, you become totally aware of the damage you do to yourself at night. There's nothing worse than that half a beer or half a drink next to you in the morning. It makes you go, '!Oh, my God, I did that!?" you know.

Does alcohol figure quite strongly in your life?

Not at all. On the airplane, two drinks and I'm totally over the moon. I'm not a drinker. I don't drink at home, I rarely drink, but a couple of drinks on a plane and, as Chuck McDermott says, I'm a cheap date. No, I'm not a drinker and luckily I was never into the drug era 'cause all my friends who were either didn't survive or bear scars. It never appealed to me and I never got a shot at consuming a lot of alcohol because two drinks and I'm on my back.

It's said that drugs changed a lot of people's songwriting.

Well, you can hear it. Drugs can be a tool. I don't use them anymore just because they don't seem to work anymore, but there was a time when I'd go and light up a joint and play a song because, when you smoke grass, there is a perception of music that is a lot different than it is when you're straight. When I smoked grass I would get paranoid, I would get hungry and sort of mute and so the only time it would work for me I would shut myself up in a room alone, light up a joint and grab a guitar. That was the sum total of it. Maybe I did it once a month. I was never a recreational drugger. I just couldn't cope with it, you know.

(Play 'All Time Woman' - John Stewart)

I'd like you to comment on another song on "Cannons in the Rain." Do you remember writing 'Road Away' because that's a very unusual composition?

Yeah, it's one of those songs that just come out of the chord progression. It just emerged.....'Well, okay, there's that fragment, what does it mean? Well, that could be this kind of story,' and the song came out of that. I wrote it inspired by Paul Simon's 'Kodachrome.' I loved the feel and the way the guitar was rolling on that record. I started playing that feel and went to a minor, and 'Road Away' just popped out of that.

But do the images relate to your life?

Not at all, it's totally made up.

(Play 'Road Away' - John Stewart)

And we move onto ''The Phoenix Concerts Live."

Oh, yeah. (Laughs)

Why are you laughing?

It was such a scene. Nik Venet once again, living on the edge with Nik Venet. Phoenix had always been terrific to me. I could sell out concerts there and the fans were always very nice, very into the music. Nik Venet quite rightly suggested that the best way to build my career was to let people around the world know that there are people who loved what I did. He said, "Let's go to the place where they love you the best and record a live album. We'll rehearse it, we'll go in, we'll record two days, no problem, no problem." So we went in and we had Jim Gordon on drums - who, at this point, was not really playing the feel that I wanted, but it was Jim Gordon so what the heck - and we had my band, and we recorded the first night. Something went wrong and we got nothing at all, absolutely nothing. That left us with one night to record a double-album. One night, one take on every song. We went in and luckily we got what we got, but the organ wasn't plugged in and so the organ you hear is leakage into another guy's mike. It was totally crazy.

Did you put any overdubs on it?

None, absolutely none. Nik said, ''No, it's a live album, warts and all. You're not going to fix it." If he let me do that I'd be fixing it still.

Do you know why you were so big in Phoenix.

Yeah, it's another example of the power of radio. That people don't know what they like, they like what they know. There was a disc jockey in Phoenix who played my records as if they were hits. So people thought that they were hits and bought my albums and turned out by the thousands to the concerts and went bonkers. It was terrific.

(Play 'The Runaway Fool of Love' - John Stewart)

I find the production on the "Wingless Angels" album rather eerie.

Well, eerie's a kind word, I think.

What word would you use?

Non-existent. Another Nik Venet album and we had a great time making it. Somehow we had tried to put the LA scene into what Nik and I did best, which was the Nashville thing. We were also under pressure to try and get something on the radio. I think there are some good songs on there. 'Survivors' is good with John Denver and the kids and all.

A lovely interplay of voices.

It worked well, yeah.

And what about the kids? Was it a children's choir?

Yeah, hired. Kids sight read like crazy, they do it all the time, they just come in and sing. It was fun to do, but it is not one of my favourite albums.

How did the song 'Survivors' come about.

Out of the political scene in America. It was more a song to myself than to other people. We're the country, it's not the leaders. The whole Nixon thing has shattered us all but we've survived much worse than this. We'll survive again because we are the country, they aren't the country. We are the country, don't let this get you down.

I know you performed the song on American TV with Ringo Starr in the chorus.

Ringo, yeah, and Steve Martin.

Was that the first time you'd met a Beatle?

I'd met the Beatles in America when they came and played in NewYork and Bobby Shane and I went backstage and talked to them briefly. Ringo didn't recall any of that, of course, and 'Survivors' was the first time we'd been around each other for any length of time.

How did you find him?

Well, to be quite honest with you, he wouldn't even give me the time of day.

(Play 'Survivors' - John Stewart)

And so you moved to RSO, the label which had the Bee Gees.

Yes indeed, and it was getting harder and harder for me to get a record label. The "Fire in the Wind" album was another production debacle. I knew it wasn't going to turn out right and so it was a question of survival of the fittest between me and the producer. I was determined that I would not crack, and that meant that if I did not crack, he would crack. One of us had to crack to get the album out of the state it was in. Finally he cracked and was taken off the project and I said to Al Coury, an old friend from Capitol Records, "Al, just let me go in and try and fix it." He said, "Okay, John, you've got $l0,000 and that's it." So I got some cheap studios and went in, and by then I knew I'd got to produce my own records. I'm really happy with the cuts I did - 'Boston Lady' and some of the other things - but "Fire in the Wind'' was never the album I hoped it would be.

(Play 'Boston Lady' - John Stewart)

'18 Wheels' is a marvellous trucking song. I'm surprised that it hasn't been picked up by some country bands.

Me too. Ronnie Hawkins did it in Canada and did a good version of it.

(Play '18 Wheels' - Ronnie Hawkins)

What about the title song of the "Fire in the Wind" album?

I love the title song. I'd love to reoord it again because I think it could be done a lot better than that. It's got a good feel to it and there's dangerous subject matter there.

That song is a real slice of American life.

It really is, yeah, and it deals with a subject that people don't like to deal with, which I like doing. It got a lot of people angry.

Was it inspired by a newspaper story?

No, it was one of those songs that came out of the title. I thought of 'Fire in the Wind' and then I was thinking what fire in the wind would be. It's totally fabricated.

The elements play quite a part in your songwriting during this period.

You mean like 'wind'? Yeah, they do. They're powerful images and they mean the same from Liverpool to Bangkok. The wind is the wind, no matter where you are. It's got a timeless element to it. They're powerful words.

(Play 'Fire in the Wind' - John Stewart)

"Bombs Away Dream Babies." This is when Lindsey Buckingham came into your life, I think.

Yeah, it is. During the "Fire in the Wind" album, Nick Reynolds, my old friend from the Trio, was down visiting me in LA and the first Fleetwood Mac album with Lindsey and Stevie Nicks on - the white album - had been recommended to us. We were playing that album all day every day. I said, "Nick, do you hear what I hear?" Songs like 'Landslide.' I was trying to play electric guitar and I had no idea how to do it. I was trying to be Keith Richards and it just wasn't working. Then I heard Lindsey play electric guitar and he was playing banjo lines, 5 string banjo lines, and I said, "Whoa, that's how to play this thing." So I started learning the electric guitar by listening to Lindsey Buckingham and really got into FleetwoodMac.

(Play 'Landslide' -FleetwoodMac)

And then you got to meet Lindsey Buckingham?

When I was doing the 'Fire in the Wind' cut I said, "Wow, this really needs a Fleetwood Mac kind of keyboard on it." (Sings) I was really into Lindsey by this time and I thought the album he produced for Walter Egan sounded sensational. I ran into Walter Egan at the Musicians' Union and I said, "What's it like working with Lindsey?" He said, "John, you've got to meet Lindsey. He learned to play off your records." I t turned out that Lindsey had learned to play off Kingston Trio albums. He knew every lick I did on every Trio song, so we got together and I said, "I'd really like you to produce my next album." He said, "Well, we're going to be doing "Tusk" but I think I can fit it in." We went into the studio and started doing things but days would go by without Lindsey coming in and he finally said, "I can't do it. I've got too much to do here. We're making a double album."

At this point RSO had assumed that Lindsey would be producing the album and I wasn't going to go through all that again with another producer, so I just let them continue to think that. I went ahead and started doing it myself and learning how the board worked. Lindsey's influence on my life was very much the same as what Elvis had done and what the Trio had done: he'd flipped a switch in my head that made the world look entirely different to me. He cranked the volume up real loud and he said, "You've got to get inside the mix, John. You've got to get inside the mix." He was playing with the EQ and the panning and I said, "Well, someday Lindsey you'll have to tell me what you're doing." He said, "I'm turning the knob until it sounds right." You know, very Zen answer. I said, "Right!" and so I lost my fear of the board and started cranking EQ like crazy, figuring out what to do.

Lindsey said, "John, you've got to do it like the old Trio records, like 'Seasons in the Sun' and 'Honey', 'Are You Mad At Your Man?' and I was trying to think, 'What does he mean?' Then, one day in a hotel in San Francisco it hit me. I mean, an actual light went off in my head and I went, 'Right. It's got to be hypnotic, it's got to be repititious, and it's got to be simple.' I called Lindsey and I said, "Lindsey, is this what you mean?" and he said, "Yeah, right."

So I went in and said, "Now I know how to do this record." I scrapped three of the tracks, went back in and learnt how to do it. I never told RSO until it was out that I'd really produced it. They thought it was Lindsey playing the guitar on there and it was me. I just let them think that, you know. When it was out I told Al and he said, "Well, it's really good, John." Then after 'Gold' was a hit and 'Midnight Wind' and 'Lost Her in the Sun' were top 20 songs and the album had gone to number 10 on the charts, no-one was going to tell me that I didn't know how to produce a record, and was having more fun than I'd ever had in the studio.

And you did an old song from your Trio days on that album.

Yeah, a song from the "Children of the Morning" album called 'The Spinnin' of the World.' Lindsey and I had just been fooling around with it and I said,"Lindsey, we should do this as a duet." So he came in and sang the harmony on it. It was just great.

(Play 'The Spinnin' of the World' - John Stewart)

It's ironic that your first hit as a solo performer should be with a song about wanting to make a hit record.

Irony

after irony, Spence, I know. I was under an edict from the record

company - if you don't get a top ten record, you are off the label.

I thought, 'What the heck, I'm going to write a hit.' Going over

to Lindsey's house in Hancock Park, this big mansion that music had done,

this all came from music, and then came the song, "turning music into gold."

Everyone at gas stations, everyone in America is either an actor or a songwriter,

and some do it and some don't. I pulled all the stops on it.

I gave it a real Fleetwood Mac sound. Lindsey played guitar on it

and Stevie Nicks came in and sang and it was an unashamed attempt to have

a hit, and it was a hit. But a lot of good it did me, and I don't

feel in any way that it's one of my best songs. The irony of pop

music is that your best things often go unnoticed while something you throw

off becomes a gigantic hit.

Irony

after irony, Spence, I know. I was under an edict from the record

company - if you don't get a top ten record, you are off the label.

I thought, 'What the heck, I'm going to write a hit.' Going over

to Lindsey's house in Hancock Park, this big mansion that music had done,

this all came from music, and then came the song, "turning music into gold."

Everyone at gas stations, everyone in America is either an actor or a songwriter,

and some do it and some don't. I pulled all the stops on it.

I gave it a real Fleetwood Mac sound. Lindsey played guitar on it

and Stevie Nicks came in and sang and it was an unashamed attempt to have

a hit, and it was a hit. But a lot of good it did me, and I don't

feel in any way that it's one of my best songs. The irony of pop

music is that your best things often go unnoticed while something you throw

off becomes a gigantic hit.

(Play 'Gold' - John Stewart)

'Lost Her in the Sun' was also a hit and that, I feel, is one of your best songs.

I do too. I love that song.

Is that a personal song?

It came from watching a baseball game. The outfield went out to get the ball and the announcer said, "Ah, lost her in the sun," and I thought, 'Wow, right!' It's a term used in baseball when you can't find the ball. In World War 2, when they were having dog-fights in fighter planes, and if they couldn't find someone in the sun, they would say, "Lost him in the sun." The rest came out of that. I thought how I could turn that into a relationship.

(Play 'Lost Her in the Sun' - John Stewart)

On a lot of your albums you don't have lyric sheets. Is that deliberate?

Well, I tell you, on the "Bombs Away Dream Babies" album I wanted to have them but Al Coury said, "They cost too much money. If we can sell half a million copies, then we'll put in a lyric sheet." So it was something I wanted but it was never included.

Tom Paxton once told me that lyric sheets took away from the construction of the song. People would finish the song before the singer did.

That's an interesting answer. I think that I like to know what the words are. If you can't understand something, it's nice to have something to follow and say, "Oh, that's what he said." I should do that. I will do that from now on.

This leads on to my next question. Lindsey Buckingham wrote and recorded a song about you called 'Johnny Stew.' I've played it several times and I still haven't a clue what it's all about. Have you been able to make out the lyrics?

(Sings) ''Everybody talking 'bout the...'', I can't really recall. I tell you how the song came about. I went by the session when Lindsey was making the "Law and Order" album. He'd a very funny guy called Richard Dashut engineering, and the song was called something else at the time. We started to make colourful names for each other. We thought my career could be resurrected if I used a colourful country name like The Amazing Johnny Stew, and Lindsey would become Liddy Buck. So he went out there and started singing, "Stew. Everybody's talking 'bout The Amazing Johnny Stew," and Richard Dashut went, "Right, that's what the song is about." Lindsey then put some words to it and I really don't know what they are either. Can you make them out at all?

No.

Right. If anyone knows, write in.

(Play 'Johnny Stew' - Lindsey Buckingham)

I hope Lindsey sounds more coherent on his new album.

I went over to see him when he was just finishing it and he played me a couple of cuts that just blew my head off. He's strung three songs together in this piece called 'Suite For D.W.' for Dennis Wilson, and that is absolutely devestating. It is so adventurous and I've never heard a record like that in my entire life. He's also got a couple of hits on the album that are just terrific.

Did you know Dennis Wilson?

Yeah.

What about all the revelations about him in Rolling Stone?

It's all true.

Was that the real side of Dennis Wilson?

To me, that's the only side of Dennis Wilson. To me, he was very hard to know.

So how did the Beach Boys maintain this lovely, clean-cut image?

Because in essence the music was like that, and Al Jardina is the sweetest man. Mike Love is a strange guy, but a very good man. He's the classic Californian punk before it was the punk it is now, you know, the street guy, cocky and hip. Now he's into meditation, but he's still a great singer and a very nice person. And Brian Wilson is one of the sweetest people you could ever meet. He was on such a roll there, he was such a genius and I don't think his mind could assimilate all that was going on inside himself. It was very sad. And then there was Dennis, who was this rogue, part of the catalyst of the group, the wild animal part, so really there was only Dennis who was the total renegade.

(Play 'Suite For D.W.' - Lindsey Buckingham)

After your enormous success with the single, 'Gold,' and the album, "Bombs Away Dream Babies," you made the album, "Dream Babies Go Hollywood," and nothing happened to it.

Absolutely nothing.

Why was that?

I don't know.

It's a very good album.

I think it's a real good album. Well, I think the wrong single was chosen initially.

What was that?

'(Odin) Spirit of the Water.'

(Play '(Odin) Spirit of the Water' - John Stewart)

What was wrong with it as a single?

Well, a lot of radio stations were playing it off the album and they wanted it out as a single, and the album lost its momentum because the single didn't take off. RSO then got cold feet about releasing the next single, which I thought should have been 'Wheels of Thunder' all along, and then it just died a natural death. RSO was in the process of dying itself, so I can't really fault them because the label was in real trouble.

(Play 'Wheels of Thunder' - John Stewart)

'Wind on the River' is a lovely track.

What a great thing it was for me to have Phil Everly come into the studio and sing on a track of mine, because I'd grown up with his music.

Did you work out the harmonies like Don and Phil, with you singing Don's part?

He came in, I played him the track, he started singing along immediately, he'd never heard the song, absolutely right harmony part. I wrote out the lyrics and he got it in one take. I said, "Phil, just for me, do the melody on one verse," and so on the master tape is an Everly Brothers version of that tune because Phil is doing parts to 'Wind on the River.' It sounds just like the Everly Brothers doing one of my songs. Beautiful. Haunting. And I sent it to Phil when he was doing his album with Don. Hopefully he'd remember and go, 'Ah, that would be a good one for us.' I guess he didn't feel it was but it was a magic moment for me to have Phil Everly in there.

(Play 'Wind on the River' - John Stewart)

Have you caught any of the Everlys' reunion concerts?

No, I haven't. I've always been in the wrong place. I saw a bit on TV and it was electric.

I saw them at the Royal Albert Hall. The audience stood up and applauded before they could even start.

Oh, my God, chills up your back, huh? What a feeling it must have been for them to walk out to that. And to have that band with Albert Lee, my God!

Have you worked with Albert Lee yourself?

No, I haven't. I would love to. He lives in Malibu part of the year and we see each other at the drug store, you know. Very nice guy. He's never been around when I've been recording. I'd just love to play with Albert Lee.

I hope listeners on Merseyside will know what's meant by "the drug store."

Oh, chemist. We don't have stores where you can go in and buy them. You have to do that on a parking lot somewhere.

What about Willie Nelson? Have you worked with him?

No, I'd love to though, I think he's terrific. I love his records, especially the ballads, they're just splendid. That album he did with 'Always on my Mind' is a great album. He phrases like no-one else, and he has an honesty and an integrity that can jump off a record. And a great guitar player, inventive and off the wall. For a country player to play those riffs and get away with it is amazing.

Many people owe a debt to Bob Dylan because he made 'non-singers' acceptable. 20 years ago Willie Nelson couldn't possibly have made it because people would have said that he couldn't sing.

Naw, do you think so? Look at the rock 'n' roll singers who made it who couldn't sing either, and the Kingston Trio really couldn't sing. Dylan took it to the next point. That is, if you can communicate you should make a record, but I think Willie Nelson is a real singer. There are a few people who are real singers and there are a lot of people who imitate singers, like I imitate singing, but I think Willie Nelson is a great singer. He's got great placement and great control.

(Play 'Always on my Mind' - Willie Nelson)

Elvis Presley originally recorded 'Always on my Mind' so I'd like to ask you about him. Did you meet him?

I met him twice, yeah. Once in Hawaii with the Kingston Trio. We did a Bell Telephone Hour that was shown the night we were there and we met one of the Memphis mafia in the coffee shop and he said, "Do you want to meet Elvis?" and I said, ''Are you kidding me?" So we went down to the movie set where he was doing "Girls, Girls, Girls!'' and there he was in a yachting cap. He said, "Oh, yeah, you're the Kingston Trio. Saw you last night. Really love your records, man." I said, "Well, Elvis, I gotta tell you. You started me on everything." He said, "Oh, yeah," and the car pulled up and he was gone.

And then we were playing in Las Vegas and I went to the lounge of the Dunes Hotel at about 4.30 in the morning. It was very dark and I was sitting at a booth having a drink and it looked like there was no-one in the place. The janitor had the electric broom going, just that sound of the whirling brush, and then I heard someone say, "Hey Stewart, alone again, huh?" I turned round and there was Elvis with four girls in a booth right behind me and I was so taken aback. I mean, there he was. When you saw Elvis Presley, there was no doubt he was Elvis Presley. Jet black hair and this incredible face and he was very lean at the time and had the right outfit on. I had spent so much time looking at those album covers and listening to those records that I turned round and totally became Woody Allen because it was (Speaks in nonsence syllables) and I couldn't say anything. I turned back to my drink and he left and said, "See you later, John." I couldn't say anything and I'd missed this great opportunity to rap with Elvis.

A friend of mine, John Wilkinson, was playing rhythm guitar for Elvis on the road and he said that Elvis used to sing 'July, You're a Woman' in the dressing room before he went on stage. He never recorded it, and it would have been the highpoint of my life to have Elvis do one of my songs, but the fact that he loved the song and sang it was enough for me. But I would have loved to have heard him do it, you know. It would have been unbelievable to hear him do that song.

(Play 'Gentle on my Mind' - Elvis Presley.....and imagine how Elvis might have treated 'July, You're a Woman')

We're getting up to 1982 and the album you made with Chuck McDermott, "Blondes." Had you known him a long time?

I met Chuck about two-and-a-half years ago. He came out from Boston. He had a country band in Boston called Wheatstraw which garnered a lot of critical acclaim, added a new dimension to country music, and he came out to California and he had a band that was playing in the LA area and we met through mutual friends. We became very close friends immediately and we work very well together. While he was doing his own thing he came in on the "Blondes" album. A very bright guy, a very talented musician and very articulate. Chuck and I really feel that we make up a total person. He's very articulate, very intuitive and very analytical, a centred person, while I'm much more of a dreamer and I have a side of madness that he doesn't have. We work very well together because the strength of each one is attracted to the strength of the other. If we were both crazy it wouldn't work, and if we were both analytical it wouldn't work, so we have a very good time together.

And Linda Ronstadt makes a guest appearance on 'The Queen of Hollywood High.' That's a marvellous track.

Oh thankyou, I really like it a lot. She's an old friend from way back from when I left the Trio days. We used to play gigs together. I'd open one night and she'd open the next, and she's remained untouched by her stardom. She remains very loyal to her old friends and remains very much Linda. In fact, she's more together now than she was in the old days.

And a fascinating song as well.

Oh thanks. An interesting tune, yeah. We thought it was going to be a single. We looked at it towards that but it remains a good song, I think.

(Play 'The Queen of Hollywood High' - John Stewart)

And how did you come to write 'Angeles (The City of the Angels)'?

It was a novelesque type of song. The story's been told many, many times in LA. Someone will come out to LA to become a star, the town's full of them, they have these dreams and it doesn't work out. They either go back home or stay in LA as a waitress or whatever, still with the yellow 8 by 10 and the bio in the closet. They remain there, tragic figures because they remain in LA. If they'd gone back to Kansas, then they'd be a waitress in Kansas. It's the arena of broken dreams that is part of the sidewalk of LA.

Like that Crickets' song, 'Little Hollywood Girl.'

Oh yeah.

You include Dustin Hoffman's name in the lyric of that song. What made you choose him?

The vowels are right. The syllables. "I know bompa bompa....." it had to fit into that. It could have been ''I know Robert Wagner,'' but "I know Clint Eastwood" wouldn't fit, you see. Dustin Hoffman, I don't know, it just worked, just popped it in there.

That verse has got a real seedy feel to it.

Oh yeah. There are guys all over town like that who claim they know somebody and actually don't. There was a terrific movie done on that theme called "The King of Comedy" that really nailed that kind of person. The remarkable thing about that film was that you hated everyone in it. There was no likeable character, which turned a lot of people off. I thought it was a brilliant movie. What a movie. That character of Rupert Pupkin is really that Hollywood guy, you know.

(Play 'Angeles (The City of the Angels)' - John Stewart)

Another of my favourite tracks of yours is 'All the Desperate Men.'

Yeah, I hope to do that again sometime. It was on the Swedish version of "Blondes" but not the American one. I don't feel I've done the right version of that yet. I think it's a real contender and I'll do it again someday.

There's a lot of resignation in that song.

In what way?

Someone who feels he's at the end of his tether.

Do you think so? You see, it's a lot different over here. The world is a global community now, but America is a very, very different country. We don't have the roots you have, we don't have the tradition, we're a nation that was started by rogues, by people that they didn't want in Europe, and that roguery is continued even to now. You go into LA and look at the architecture. It's a ludicrous country. There can be a beautiful Spanish building right next to a little cafe that's made in the shape of a hot dog. We're very desperate over there. Success is very important in America and everything is up for grabs, everything is always being tested. We have a real lack of tradition, a lack of roots, a lack of discipline, and America is really 'All the Desperate Men.' It's not really that autobiographical.

But you're a couple of hundred years old.

That it should remain, yeah, but we don't have a building that's been there for 400 years. We're so homogenised now. You can go to San Jose, California, or Dubuque, Iowa, and they look essentially the same with their new architecture and billboards and the restaurants, Thank God It's Friday, and trendy little places that all look exactly the same. It's a very disposable country.

(Play 'All the Desperate Men' - John Stewart)

Last year you made an album with another former member of the Kingston Trio, Nick Reynolds. Why did you call it "Revenge of the Budgie"?

Budgie was Nick's code name in the Trio days. He was always known as Budgie. He hadn't recorded in 16 years. Bobby Shane, the other member of the Trio, was out singing with a group called the Kingston Trio and I'd been working but Nick had been in the background. So we were going to call it "Return of the Budgie" and I said, "No, no. Revenge of the Budgie," and he said, "Yeah!"

And why did you call him Budgie?

It just happens. When you're thrown together on the road 200 days a year, you go into your right lobe and this craziness comes out, little code names and things. You have just to keep yourself sane within your insanity. He was just the Budgie, he was short and gnome-like, you know.

My favourite track on the album is 'Dreamers on the Rise.'

Me too. I think it's one of the best songs I've ever written. I did a version with Chuck that I thought was very good. Then when Nick heard it he said, "Oh, we've got to do this song," so we did it. I'm very happy with that song.

(Play 'Dreamers on the Rise' - Nick Reynolds and John Stewart)

Your latest album is "Trancas." What does it mean?

It's an Indian name. I don't know what it means, but I recorded the album in a studio in the Trancas Canyon in Malibu. I was living in Trancas and the bar where Chuck would play and I would go and sit in is the Trancas Bar and Grill. So "Trancas" was an obvious name for the album.

I presume that 'It Ain't the Gold' is the answer to the success that you had with 'Gold.'

Well, it is. In essence what is really important is not the medal, not the winning, but just doing it. I've always known that but it became very real to me that the real fun was in doing it. Getting the reward is not as rewarding as it appears to be. If you don't have fun doing it, you never will have fun.

I haven't made out all the lyrics, but is that a reference to Errol Flynn?

"Here's to Errol Flynnin'," yeah! Errol Flynn was the great, devil-may-care movie star, swashbuckler, live for today, the devil take tomorrow, just go out and do it. That's what it means - don't think about it, just do it.

(Play 'It Ain't the Gold' - John Stewart)

Another great song on that album is 'Chasing Down the Rain.'

Oh, thank you. Buffy and I were separated at this time for a good long period, and out of pain comes a lot of good songs.

And a reconciliation.

Luckily, yes, we're back together now, very happy.

(Play 'Chasing Down the Rain' - John Stewart)

And 'Reasons to Rise.'

'Reasons to Rise' is, I think, one of the best songs I've ever written. I think it really nails what that is.

(Play 'Reasons to Rise' - John Stewart)

Also on "Trancas" you do 'Rocky Top,' the first time for many years that you've done a song by somebody else.

Have I ever?

Not since the Trio days. So what made you change your mind?

I was sitting at home with a drum machine and the arpeggiator on my synthesiser that you can plug into the drum machine and play notes that play right along with you. I was playing the guitar and I started singing 'Rocky Top' and I went, 'Whoa, that sounds great.' 'Rocky Top' is 'Rocky Top.' It's a classic song and it was pointless for me to write a song to fit that groove when 'Rocky Top' did it in spades. I've always loved 'Rocky Top.' It's one of the great choruses, one of the great feels of all-time as far as a song living forever.

Is there a particular version you like?

No.

There's

a version in Japanese.

There's

a version in Japanese.

(Does Japanese accent) Oh, 'Locky Top.' I've known the song for years but I don't have it on a record by anybody. It's just a song that's always been there and I've always known it.

(Play 'Rocky Top' - John Stewart)

Finally, I'd like to ask you about Omaha Rainbow. It must be very flattering to have a magazine named after one of your songs.

Incredibly flattering, and it's very good and very unconsumed with relevant commerciality. Peter O'Brien writes about what he thinks is good and what he likes. I'm sure Joe Ely is known in the UK because of Peter. I find the interviews in Omaha Rainbow more fascinating than the interviews in Rolling Stone because people like Joe Ely and T-Bone Burnett aren't as on guard as they would be with a major publication. I think they say things and give things out to Omaha Rainbow that you would not get in the major press simply because it is a small, little rock magazine. I think, as the years go by, The Rainbow will be referred to historically as real accurate material on some artists.

(Play 'Omaha Rainbow' - John Stewart)

![]()